Heading Title

Introduction

Guess what – chickens are biologically set up to make life difficult for dinner. They have this wonderful gelatinous meat in their legs and thighs, crispy and flavoursome wings and wingtips – assuming they have roasted well – and chicken oysters, those incredible little jewels of tender meat sat behind the legs. Everything is wonderful until you get to that grainy, feather-spitting breast meat which I’ve watched my kids masticate until they’ve lost the will to eat.

But it doesn’t have to be like this. In fact once you get to understand a little more about our feathered friends, and in particular their anatomy, you will be on track to being able to cook the most delectable roast chicken ever; and I promise you, you’ll be scrambling to get that newly discovered succulent breast meat.

Heading Title

Why is the Moist Meat Moist and the Dry Meat Dry

To understand why some chicken meat is moist while other parts turn out dry, we first need to delve into the textures of different cuts. Understanding these differences is key to knowing how to cook each part and choosing the right method for your dish. This is especially important when cooking a whole bird, where the challenge is making sure all the meat—from breast to thigh—stays moist and tender.

With that knowledge, cooking chicken stops being a gamble and starts becoming a craft. So let us, together, take an adventure around that humble chicken to understand what it’s made up of. We’ll start at the bottom and work our way up.

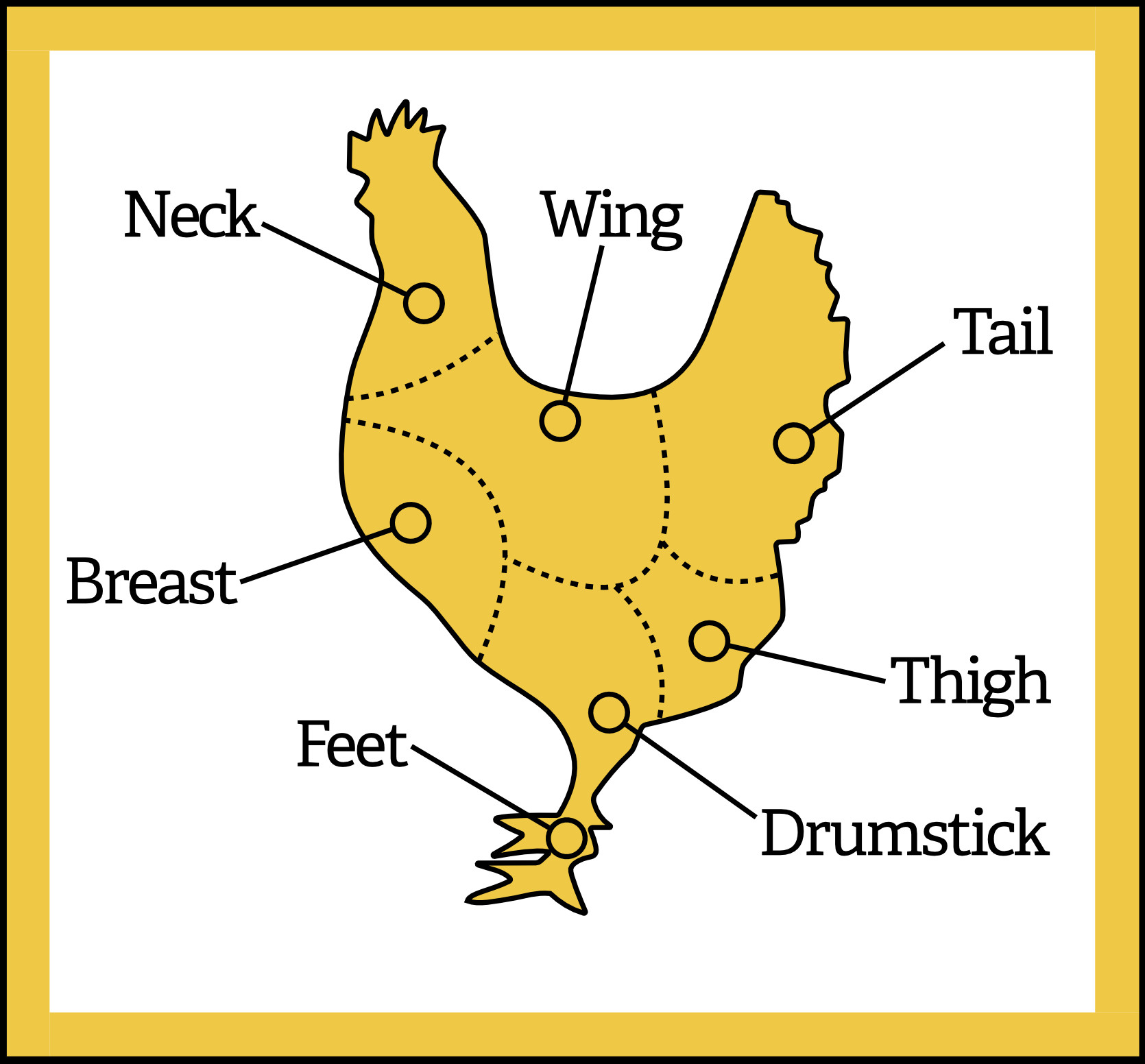

Feet first — these gnarly, bony things have more joints than a 90s rap video. There is barely any meat on them, but when simmered in a black bean sauce or deep-fried until they puff and crisp they’re absolutely fantastic. It’s all about the gelatine within, which we will come on to later. You don’t eat chicken feet for the flesh; you eat them for the texture and the sauce that clings to them. It’s a guilty pleasure., believe me.

Next, the drumsticks. These are your dark, moist food bombs that everyone wants. All that connective tissue—collagen, to be precise—breaks down in to gelatine when heated past the magic 73°C/ 163°F mark and gives you that juicy, sticky texture that makes your fingers shiny and rips your serviette to shreds when you try and clean them. Drumsticks are great roasted, even better when marinated, and wonderfully irresistible when glazed in something sticky-sweet like honey and soy sauce.

Now the thighs. Connected to the legs are the thighs which are cooked either with the bone in or out. The meat is similar to the drumstick and so requires cooking to above 73°C/ 163°F otherwise it will be chewy because the collagen won’t have broken down. The thighs are the workhorses of the chicken – versatile, forgiving, and fantastic in just about anything from curries to stir-fries; and exceptional deep fried with a creole seasoning.

Then, the oysters. These are the often missed parts of the chicken because they are so small. Essentially, they are two small muscles that sit just at the back of each thigh on the spine. I like to think of their texture as a cross between breast meat and thigh meat; the best of both worlds. A firm meaty texture that when cooked to the right temperature have a mildly gelatinous texture. It’s regarded as the best part of the bird, being full of flavour and firmer than the other parts of the bird. Traditionally the person that cooks the chicken gets first refusal on these magnificent tidbits.

Now, to the troublemaker — the breast. The cut that makes or breaks reputations. It’s the part of the bird which should be the most sought after; plump, pristine and proudly sitting in the spotlight. Unfortunately, it is often overcooked by a few degrees, especially when roasting the chicken as a whole. This results in an experience akin to chewing on dehydrated sandpaper, and also being the part selected last at the dinner table; like a penny toffee in a tin of Quality Street. It shouldn’t be that way though, it should be the shining star; succulent, moist and the most prized. The secret is to ensure that it is not cooked beyond 67°C/ 153°F. As the breast doesn’t do much work during the bird’s life, unlike the legs, wings and thighs, it doesn’t contain much connective tissue and thus produces very little gelatine when cooked. It’s therefore less resistant to overcooking than the other parts of the bird.

And the wings and wing-tips. These are often marinated and roasted, or more commonly seen deep fried with a herby coating until crisp. The meat is similar in texture to that of a drumstick although they do have very little meat on them. The wing is considered to be the most flavoursome part of the bird (the wing-tips when roasted on the whole bird are seriously good). The wings and tips are also really great for adding flavour to stocks, broths and sauces.

Lastly, the neck and head. Not seen much in the Western kitchen, but elsewhere they’re common, especially in Asia. If you do have the neck and head on a bought chicken they are great to flavour stock or broth.

Heading Title

The Secret to a Perfect Whole Roast Chicken

Roasting a whole chicken presents a challenge. As we have see the outer parts – wings, thighs, and legs – benefit from higher heat to break down the collagen (connective tissue) into rich, sticky gelatine. The breast, on the other hand, is lean and delicate, and prone to drying out if exposed to the same heat intensity.

Breaking the chicken down and cooking the parts individually does allow for more control – but sometimes, roasting the bird whole is the goal. So, how do you manage the different needs of each cut whilst still producing an evenly cooked result?

The key is understanding what you’re aiming for:

- Golden, crisp skin

- Soft, gelatinous dark meat (the wings, thighs and legs)

- A succulent, moist breast, cooked through but never dry

Heading Title

1. Use a probe thermometer – the real game changer

The most reliable way to avoid undercooking or overcooking is by tracking the internal temperature of the chicken. As we said the dark meat requires around 73°C/ 163°F for the connective tissues to break down into gelatine. It can cope with a little higher temperature without drying out. The breast, however, is much less forgiving – pulling it out of the oven at 67°C/ 153°F gives the best results. Resting for 10 minutes or so will carry it through to a safe final temperature while keeping it tender and juicy. Using a probe thermometer allows you to accurately track the internal temperature of the breast, ensuring precise doneness and preventing overcooking.

Heading Title

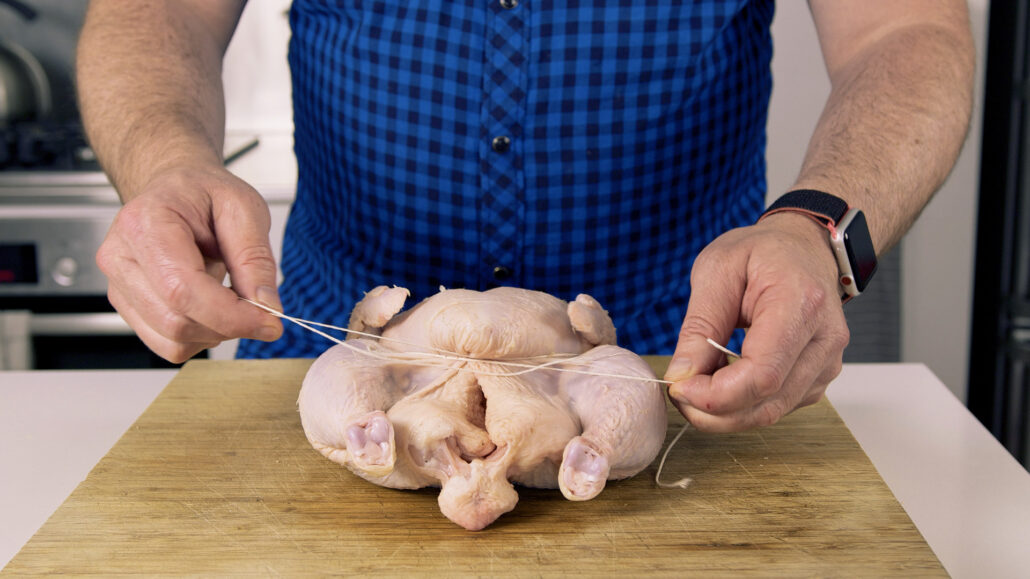

2. Truss the chicken

Trussing is a method of tying up the chicken to make it compact – so that the legs and wings are kept securely next to the main body.

Why Truss? The main reason to truss a bird is to get a juicy, evenly cooked bird with a golden brown crispy skin when roasted. The theory is that by being compact there is a more uniform heat distribution throughout the bird when cooking it. This reduces the chance of overcooking and drying out the wings and drumsticks whilst also helping to keep the breast meat moist

Heading Title

3. Barding (if used carefully)

Barding involves wrapping the bird in thin slices of bacon or pork fat before roasting. The fat renders during cooking, adding moisture and flavour. With chicken, however, the balance is delicate – the bard should complement, not overwhelm. Use it sparingly and with consideration for the final flavour profile.

Brining is another option, which involves soaking the chicken in salted water for a period of time and then rinsing in a number of changes of water and then drying the chicken in the fridge overnight. This is a very good technique when it works; may be something for another post!

Considerations When Roasting Whole

Roasting temperature and time have a significant impact on outcome. High heat from the start can produce great skin, but risks drying the breast. A low, steady roast gives more even results but may not brown the skin properly.

A two-stage approach works well:

- Roast at a lower temperature 180°C (360°F) to allow even cooking through the bird, then finish with higher heat 220°C (430°F) to crisp the skin and deepen the flavour.

- Basting during roasting helps enhance moisture and flavour. This can be done with the bird’s own juices, melted butter, or a light marinade brushed over the surface periodically. Basting encourages a rich, glossy finish and protects the skin from drying out too quickly.

Use a shallow roasting pan. This allows hot air to circulate freely, resulting in better browning and a more even cook. Elevating the bird slightly – either on a rack or on halved onions or other vegetables – ensures heat reaches underneath. The vegetables, once roasted, also provide a great foundation for sauces or gravies.

Avoid adding liquid to the roasting pan. Water or stock in the base will steam the bird, softening the skin and giving the meat a boiled flavour. Roasting is a dry heat method, and maintaining that environment is key to achieving the desired texture and taste.

Heading Title

The Roast Is Just the Start

There’s a lot to think about when it comes to cooking the perfect roast chicken—temperatures, timings, trussing, thermometers, and choosing the right method to suit the bird. But once you get your head around it, it becomes second nature. It’s one of those foundational dishes that, when done well, gives you confidence in the kitchen.

If you want to go deeper, I run a full Masterclass in Preparing, Butchering and Cooking Chicken—a course built for home cooks who want to take their skills to the next level. In it, you’ll find that perfect roast chicken recipe, plus much more.

You’ll learn everything you need to know about handling, preparing, butchering, and cooking chicken like a pro. I cover the whole bird—inside and out—so you can cook with confidence, waste nothing, and turn even the simplest cut into something special. You’ll not only learn how to roast but also cooking techniques from braising, pan-frying, and barbecuing to poaching, stir-frying, and grilling.

There’s no window dressing—just real, hands-on techniques. From choosing the right bird and storing it safely, to breaking it down, jointing, trussing, and even deboning the entire chicken, you’ll learn skills that stick for life.

And of course, you’ll cook. A lot. We go from Cajun-style fried chicken and crispy schnitzel to stuffed roast with braised vegetables, zesty lemon basil chicken with crushed feta potatoes, and a standout ballotine with duxelles and cream sauce. There’s *emongrass chilli chicken, warming pho ga, and Italian-style chicken meatballs in tomato sauce—plus how to build flavour from the ground up with both light and dark chicken stocks.

It’s the kind of course that changes how you think about chicken—and how you cook, full stop.

If that sounds like something you’d get a lot from, check out the full masterclass

https://courses.duckandroses.com/

Let me know how your roast chicken turns out—feel free to ask questions or share your own tips in the comments below. And if you’re ready to truly master cooking chicken, be sure to check out the course. Bon appétit!